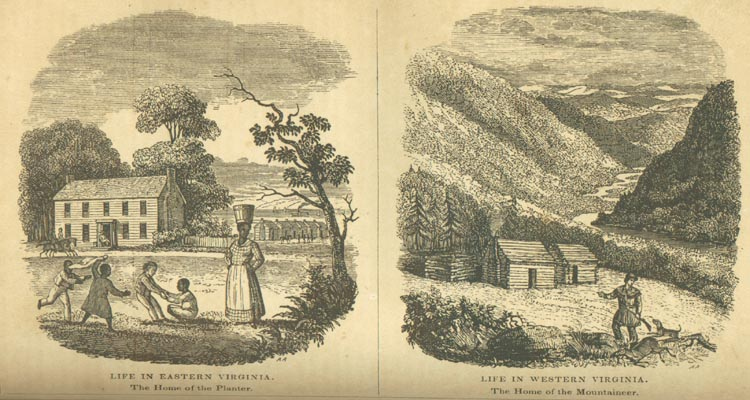

Virginia, which then comprised both Virginia and what is today West Virginia. On June 20, 1863, West Virginia became the 35th state in the Union after Congress, President Lincoln, and voters approved the separation. The division was contentious, but had roots in conflict as far back as the 1776 Virginia Constitution. As you examine this image, published in prominent author and publisher Henry Howe’s Historical Collections of Virginia in 1852, consider how it portrays the differences between eastern and western Virginia.

Tension between eastern and western Virginia before the Civil War centered on politics and economics. The initial Virginia Constitution favored eastern Virginia by granting voting rights only to white men who owned 25 (improved) or 50 (unimproved) acres of land. This provision discriminated against small landowners in western Virginia, and those who did not own the land on which they lived. The Constitution also apportioned only two delegates per county, regardless of population, and only four of the state’s 24 senate districts lay in western Virginia. Cultural differences were also evident. Western Virginians celebrated their “mountaineer” identity as opposed to the genteel, eastern “planters” – a divide illustrated this image.

Some of the earliest calls for secession began in 1829, after eastern Virginia conservatives defeated a popular referendum to the state constitution that would have instituted white male suffrage, representation based on white population (since there were few slaves in western Virginia, this would have balanced representation), and the direct election of state and local officials. While constitutional reforms in 1850, as well as some state-sponsored infrastructure projects, eased tension, it remained at the surface as sectional conflict increased nationally in the 1850s and 1860s.

Disagreement peaked again after Virginia voted to secede from the Union on April 17, 1861. Delegates from western Virginia opposed the decision and organized a convention in Wheeling, western Virginia, to discuss their options. The First and Second Wheeling Conventions established the Reorganized Government of Virginia to replace the now Confederate government of Virginia, and then proceeded to debate creation of a new state in western Virginia, which they initially called Kanawha.

After voters in western Virginia approved the plan to organize a new state, the measure moved to debate in the U.S. Congress, which focused on the question of slavery. The western Virginia delegates had chosen to keep slavery legal, but Republican Congressmen opposed this decision. They compromised on gradual emancipation.

President Lincoln, after debating the issue carefully, signed the statehood bill in the interest of securing the loyalty of western Virginia. West Virginia’s first governor, Arthur Boreman, stated in his inaugural address that “to-day after many long and weary years of insult and injustice, culminating on the part of the East, … we have the proud satisfaction of proclaiming to those around us that we are a separate State in the Union.”

Source: Henry Howe, “Life in Eastern Virginia; Life in Western Virginia,” in Historical Collections of Virginia, by Henry Howe (Charleston, SC: Wm. R. Babcock, 1852), 152 facing, accessed September 20, 2011.