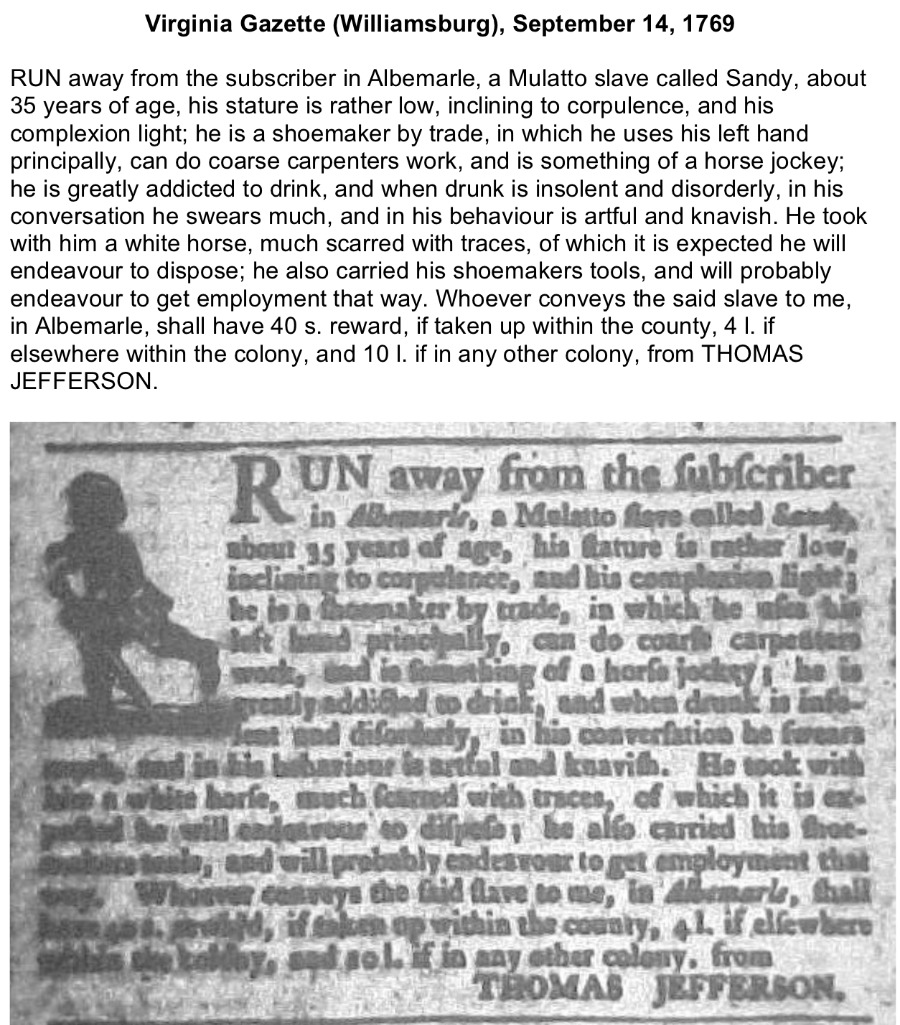

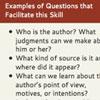

In September 1769, Thomas Jefferson drafted an advertisement for the Virginia Gazette soliciting the return of one of his slaves who had escaped. Almost everything we know about the runaway, Sandy, emerges from the advertisement below. He was left handed, skilled in carpentry, “artful and knavish” in his behavior, and valued with a reward of 40 shillings. The full details of his life, like countless other Americans of the era, are otherwise lost to history.

This runaway advertisement stands in contrast to an image of Thomas Jefferson more familiar to most Americans – the Thomas Jefferson in June of 1776, quill pen in hand, as he drafted the stirring opening to the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson wrote that all men were created equal, endowed with the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The dissonance in the two scenes – one a soaring paean to human freedom and dignity, the other harsh evidence of one man owning another – reveals a lot about the ways in which we think and teach about the past. The first is that history is far messier than we often acknowledge. That the same individual penned both pieces forces us to confront the complexity and apparent inconsistencies of a celebrated historical figure.

The second is that an understanding of history built solely on the stories of the renowned is fundamentally incomplete. We know far more about the Jeffersons of the past than we do about the Sandys, even though ordinary Americans such as this runaway slave played an enormous role in shaping the nation.

Placing original documents like the Declaration and Jefferson’s runaway advertisement in students’ hands requires them to think critically, fostering an eagerness to learn more about the complexities and contradictions in our nation’s past that were as real centuries ago as they are today. It inspires students to learn on their own and to become more active consumers of historical narratives.

Presenting students with a series of names and dates to memorize, as do so many textbooks, leads many students to classify history as boring and irrelevant; encouraging students to embrace the messiness of the past and the full range of its participants engages them in critical thinking and self-motivated learning.

Source: Thomas Jefferson, “Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon),” Gazette (Williamsburg, VA, September 14, 1769), in The Geography of Slavery, accessed September 16, 2011.